Official Memorial Policy – Votive Church of Mohács

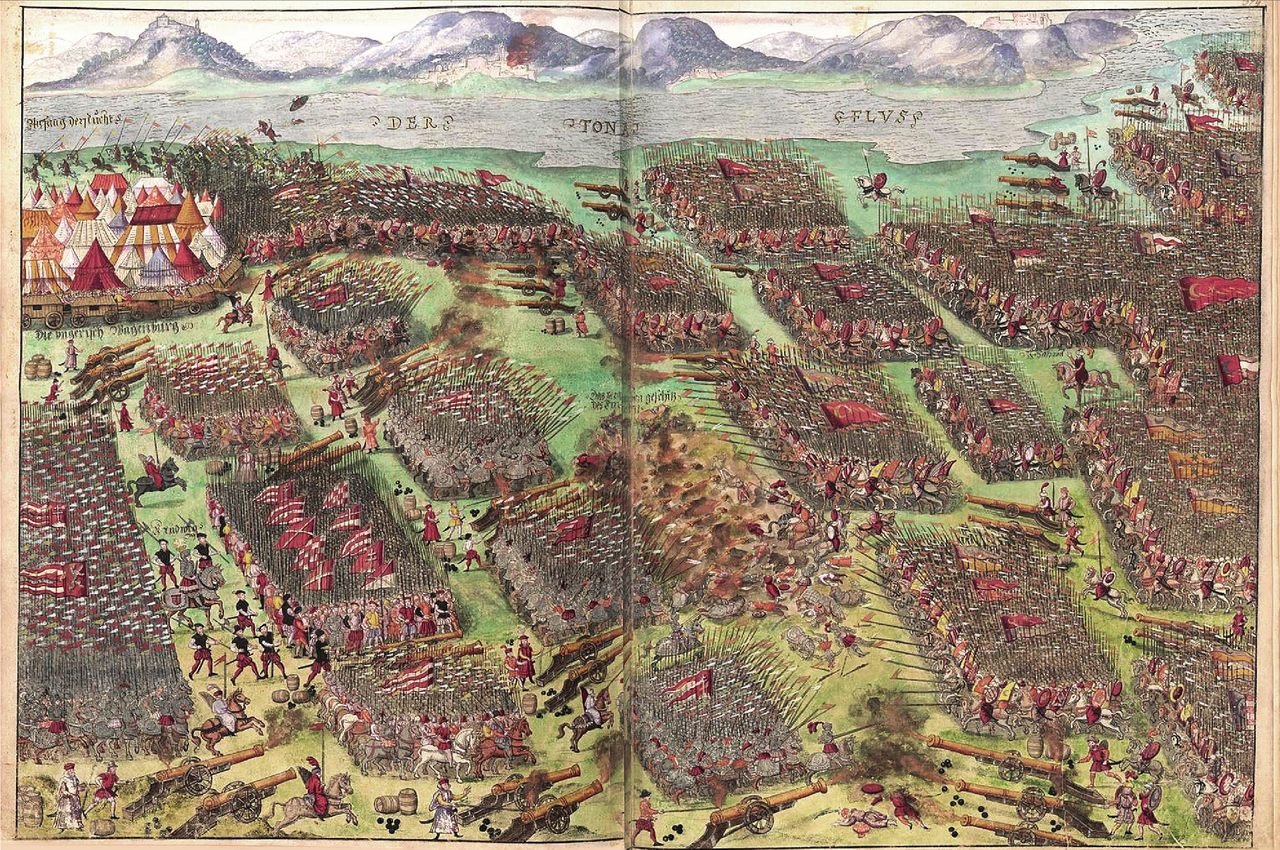

Fact of the Hungarian figure „The vast cemetery of our national greatness” – The Battle of Mohács”

Part of the „The myth of national disaster” topic

The Votive Church of Mohács not only serves as a symbol of remembrance for the Battle of Mohács but also reflects Hungary’s complex historical memory and its evolution over the centuries. The church was first dedicated on the 400th anniversary of the battle in 1926.

The historical coincidence of the collapse of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary after the disastrous Battle of Mohács and the spread of the Reformation in Hungary made it inevitable that the causation of the national disaster would, sooner or later, take on a confessional character. During the turbulent years of confessionalization and the following decades of brutal persecution of non-Catholics in the Habsburg Monarchy, the Battle of Mohács became a significant issue in the discourse on national decline. Naturally, confessional scapegoating emerged as a recurrent feature of both Catholic and Protestant historiography and denominational debate. The historiography of the period tended to focus on agitation and was concerned with identifying internal and external enemies responsible for the decline of the realm. This can be seen in the works of Catholic authors such as István Székely and those of Protestant intellectuals like Gáspár Heltai. The Protestant narrative held the Catholic elite, both secular and ecclesiastical, accountable. In their view, the Catholic prelates and nobility weakened the Jagiellonian state economically and politically through their greed and corruption. Furthermore, the Catholics brought the wrath of God upon the kingdom with their sinful ways. Due to the shameless acts of the Catholics, the Ottoman conquest struck the Kingdom of Hungary as a terrible spectacle of divine retribution.

In early 19th-century Hungary, the memory of the Battle gained new significance. During the Reform Era, the defeat was reframed as a national tragedy and a symbol of historical decline. Following the failed 1848–49 War of Independence, writers and historians increasingly portrayed Mohács as a metaphor for foreign oppression and lost sovereignty, drawing parallels between the 1526 defeat and Habsburg domination. This interpretation remained powerful throughout the existence of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. Mohács became embedded in Hungary’s national identity as a point of historical rupture, symbolizing the country’s struggles for freedom. The phrase “More was lost at Mohács” gained widespread use, expressing both personal loss and collective trauma. In literature, public memory, and political discourse, Mohács served not only as a military event but as a lasting emblem of the nation’s desire for autonomy and historical justice.

The 450th anniversary of the battle in 1976 marked the completion of the church as part of Hungary’s official memorial policy under a communist regime that aimed to reinterpret national history. While the communist authorities downplayed nationalist sentiments, the memory of Mohács remained a powerful undercurrent in shaping national identity. The battle, symbolizing a tragic loss and the beginning of foreign domination, resonated with themes of resistance and survival that aligned with the regime’s narratives of struggle against oppression. As Hungary approaches the 500th anniversary of the Battle of Mohács in 2026, the Votive Church of Mohács remains a key site of memory.