„No. No. Never.” – Treaty of Trianon – Monument of National Solidarity – Budapest

Hungarian figure of the „The myth of national disaster” topic

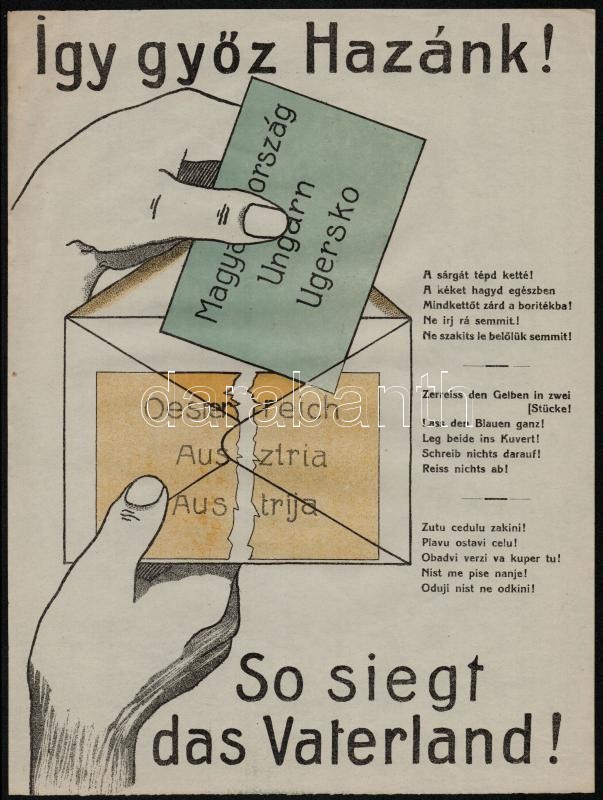

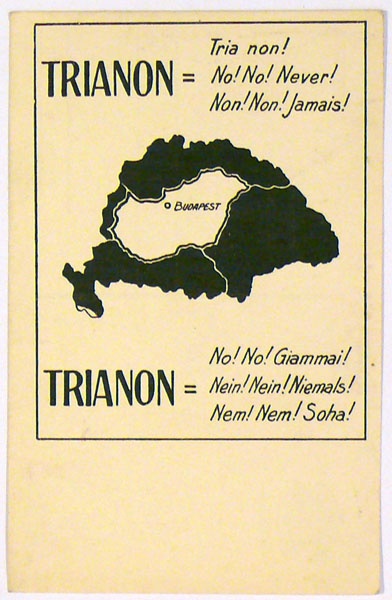

“No. No. Never.” – Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon, signed on June 4, 1920, remains one of the most contentious and painful moments in Hungarian history. This treaty, which concluded World War I for Hungary, resulted in the loss of nearly two-thirds of its territory and about one-third of its population. The phrase „No. No. Never.” encapsulates the deep-seated rejection of the treaty by the vast majority of Hungarian society, reflecting the national trauma and enduring sense of injustice that it engendered.

In 2020, on the centenary of the Treaty of Trianon, the Monument of National Solidarity was inaugurated in Budapest. This modern memorial, located near Kossuth Square and next to the Parliament building, was designed to honor the memory of those who suffered the consequences of the treaty and to symbolize the unity of the Hungarian people across borders. The monument is a stark, minimalist structure, featuring a 100-meter-long ramp descending into the earth, lined with the names of the 12,537 towns and villages that were part of historic Hungary before the treaty. At the end of the ramp, an eternal flame burns, symbolizing the enduring spirit of the Hungarian nation.

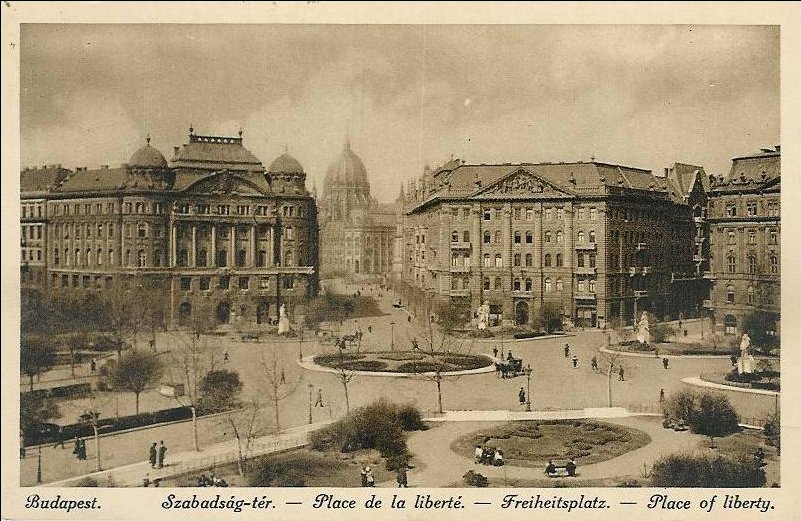

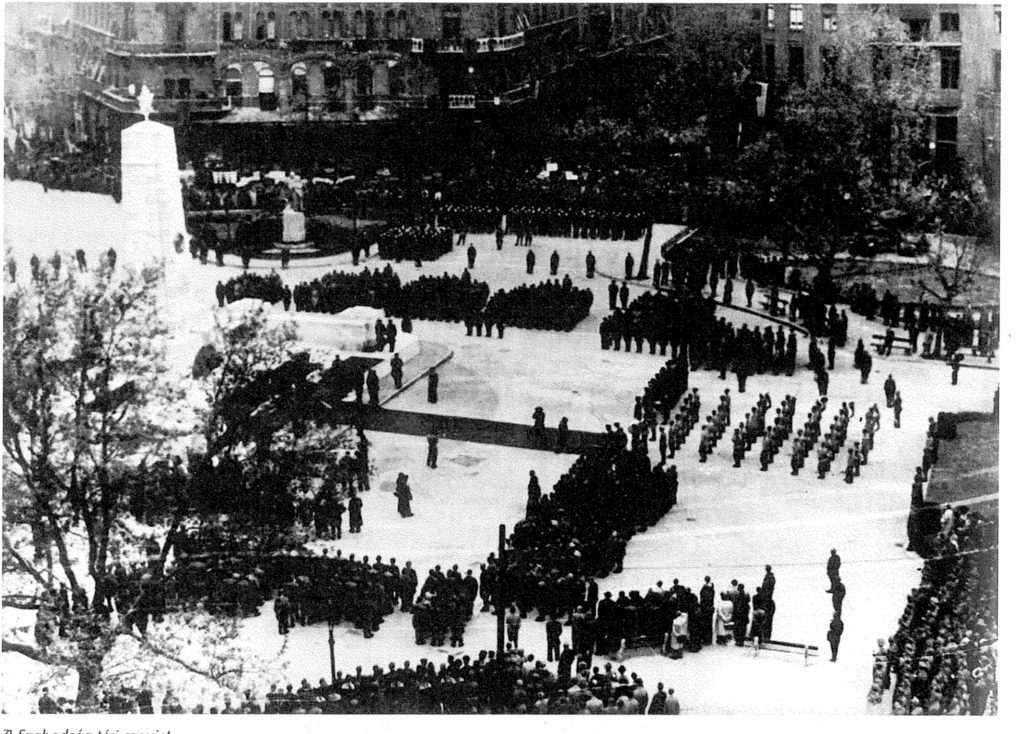

This new monument replaced an earlier, more controversial memorial that once stood in Liberty (Szabadság) Square. The original Trianon memorial, erected in 1934, was a grand structure topped with a statue of Archangel Gabriel, symbolizing Hungary’s divine right to its territories. However, after World War II and the establishment of the communist regime in Hungary, the monument was dismantled in 1947 as part of the Soviet-backed government’s efforts to reshape Hungary’s national identity and suppress symbols of its pre-war past.

The creation of the new Monument of National Solidarity in 2020 reflects the Hungarians’ need for symbolic unity with fellow Hungarians beyond the state’s borders. The monument serves not only as a reminder of the Trianon Treaty but also as part of a broader dialogue in the region regarding national identity, historical memory, and the long-term impacts of geopolitical shifts. Similar memorials and monuments can be found across Central Europe, where various nations have commemorated their own losses and traumas from this period. The complexity of this issue lies in the fact that what constitutes a significant loss for one nation can be seen as a joyous celebration for another. For example, in Slovakia, Romania, and Serbia—countries that gained territory from Hungary due to the treaty—monuments celebrate national victories and the „unification” of their lands. These monuments are often viewed as mirrors of the Hungarian experience, highlighting the complex and often contradictory narratives that emerged from the Treaty of Trianon.

The Treaty of Trianon and its aftermath remain a sensitive and polarizing topic not only in Hungary but also in its relations with neighboring countries. While the Monument of National Solidarity in Budapest is intended as a symbol of remembrance and unity, it also serves as a reminder of the ongoing challenges in Central European diplomacy and the region’s complex history of shifting borders and national identities.

Facts