Central Europe: The Landscape Dedicated to Myths

As far as we can judge, the Central European nations attached particular importance to myths not only in the Middle Ages but also in modern times, and their function remained the same. From the beginning, they sought to name the position of these nations in the history of Christian, then European, civilization. Only their content changed. The earliest known myths defined the role of nations in the story of salvation, gave them a right to the lands they inhabited, and established, usually negatively, their relationship to their neighbours. In the centuries that followed, they helped to shape public opinion, to defend shared values and, from the 19th century onwards, to mobilise public opinion against internal and external enemies. The poorly developed state structures that are characteristic of Central Europe then lent mythical narratives a special, normative significance.

Central European myths replaced the functional state for the local peoples and told stories in which good regularly triumphed over evil, the weak over the strong, honesty and common sense over the cunning and tinsel of the big world. At the same time, however, Central European myths were shared exclusively within tight national frameworks, and often saw their neighbours as usually insidious enemies. They thus bear witness to the various forms of Central Europe, German, Austrian, Czech, Polish or Hungarian.

Unity in diversity, however, has been evident since the early Middle Ages. While Czech myths explained social orders, Polish myths emphasized the nation’s firm place in the great story of salvation, and Hungarian myths defended the right to homeland. There was also the black legend of the fall of the Mojmir dukes, which warned, with surprising urgency in Hungary and Bohemia at the same time, against the improper way of governance as early as the 12th century.

Johnson, Lonnie R. Central Europe: Enemies, Neighbors, Friends. Oxford University Press, 1996.

Geary, Patrick J. The Myth of Nations: The Medieval Origins of Europe. Princeton University Press, 2003.

Wihoda, Martin. The Making of Medieval Central Europe: Power and Political Prerequisites for the First Westernization, 791–1122. Rowman & Littlefield, 2024.

Myth of the Hungarian land-taking – Ópusztaszer

The Ópusztaszer National Heritage Park is a site of profound historical and cultural significance. It commemorates the mythic and historic events surrounding the Hungarian land- taking (honfoglalás). This park serves as a living museum, preserving and presenting the heritage of the Hungarian people from their early tribal origins to the establishment of a homeland in the Carpathian Basin. The story of the Hungarian land- taking is rooted in the 9 th century when the seven Hungarian chieftains, led by Árpád, guided their tribes from the steppes of Eurasia into the Carpathian Basin. This monumental migration is not only a cornerstone of Hungarian national identity but also a crucial chapter in the history of Central Europe. The Ópusztaszer National Heritage Park embodies this narrative, offering visitors a tangible connection to this legendary past.

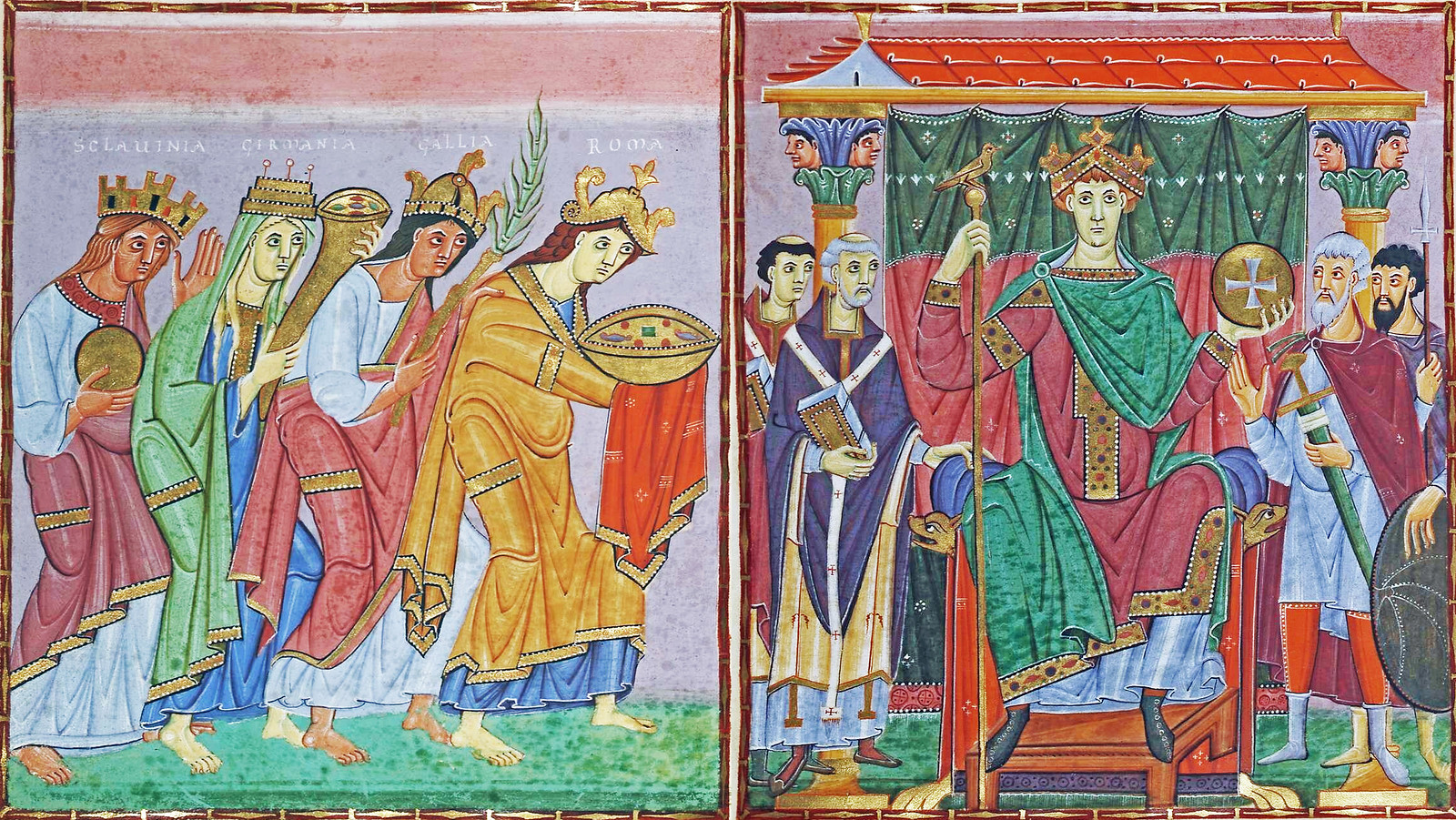

Polish national myths – Gniezno Cathedral

Myths and legends are the backbone of any national identity. In the case of Poland, many of these originate from tales older than the earliest written sources referring to the Piast dynasty and their realm – tales of ancient woods and native, tribal people inhabiting them. These stories, full of pagan magic and miracles, were remembered and even maintained through times of Christianization, when monks and scholars adopted them into the first chronicles of the state. New era and new religion also provided fertile soil for new legends – old magic was replaced with divine intervention. Still, the idea of using those tales to strengthen the nation’s spirit remained.

Three Lives of Czech Myths – Prague

Who the Czechs are and why they became a politically active community sharing the same values are questions answered in the early Middle Ages by myths written down at the end of the 10th century. The dean of St Vitus, Cosmas, gave these myths a canonical form shortly before 1125. He placed the Czechs among God’s chosen people, born out of the flood and the confusion of tongues. Then he granted them the right to the land, claiming that Forefather Čech had brought the people to the foot of the Říp mountain, to an empty land not yet cultivated by anyone. However, he devoted the most space to the legend that legitimized the rule of the dynasty of the mythical Přemysl the Ploughman.